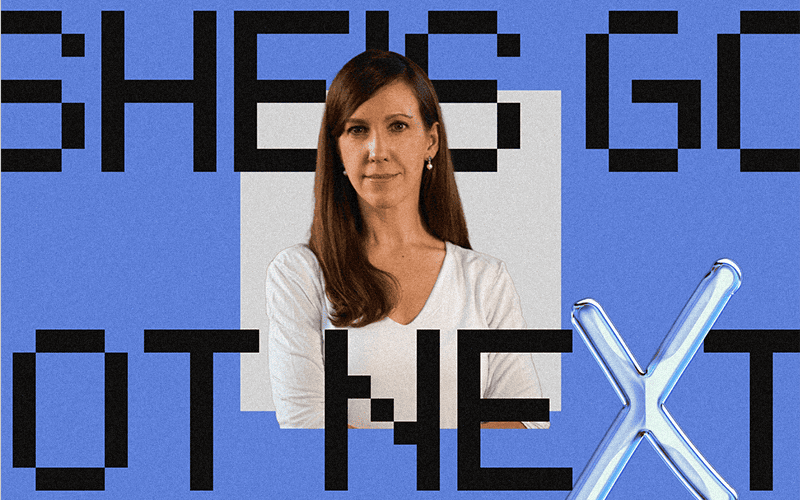

She’s Got Next: Kathryn Bertine

An author, athlete, activist and documentary film maker, Kathryn Bertine has been on the forefront of advocating for equity for women in professional cycling. Instrumental in the movement that successfully lobbied the Tour de France to include women in the sport’s signature competition, she continues her work on the gender pay gap through her non-profit, Homestretch Foundation.

This conversation is edited for length and clarity.

Women have long been neglected in the sport of cycling – in opportunity, prize money and sponsorship. What was the tipping point for you that made you say, “I have to do something?”

What I have seen in the past is that change comes from those who are in the arena. When we look back, we see that Billie Jean King could create change while she was playing tennis, because she was experiencing those exact hurdles in her sport at the time. The same thing with women’s soccer and women’s ice hockey – they were lobbying for change and pay equity and it came in part because the work was being done by athletes who were currently playing the sport.

I knew when I was in cycling and racing things weren’t right. If I ever want to see change during my lifetime, while I’m engaged in this sport, then it had to come from me and others while we were playing the sport. Even now, as an alumna of pro cycling, I can still help affect change, but the next round of change will come from the women who are currently playing as well.

That was the key turning point where, like so many of us, I thought that change just happens. But no, change doesn’t have to happen. People must stand up and speak out and make change happen. Maybe in the beginning, I thought, “Oh, someone has to change this!” and then it very quickly became apparent, oh, wait, that’s me. And that’s the other women in the sport, too.

I was lucky enough to make it to the World Tour level of pro cycling, but I was not a world champion. I was not an Olympian. I didn’t have a plethora of gold medals around my neck. And what’s amazing about that is if I were able to create that change, then it should serve an example that we are all able to create change. That’s something I always try to drive home. You don’t have to be wealthy or famous, or a gold medalist or an influencer with millions of followers to make something happen. You can create change by connecting with other people who are in a similar position to you, create a team and a game plan. That’s how we got the ball rolling. At first, I tried doing this stuff by myself, but it kind of fell on deaf ears until there was a team of us that banded together to stand up and fight for change.

A victory came on July 27, 2014 when the pro women of road cycling raced on the Champs-Elysees two hours before the men’s Tour de France concluded their final stage. What was that moment like for you?

That moment was surreal and wonderful on a few different levels. As an athlete, I was able to race and stand on the start line of my dream. It was incredibly meaningful to be part of that day.

As an activist and advocate for change, it was equally meaningful. It was not lost on me on the bigger picture of what we had created. I think age plays a part in that, too. The day I stood there on the Champs-Elysees, I was 39 years old, and we had fought really hard for what happened. Maybe if I had been my 21- or 20-year-old self, it would have felt different. We had plenty of young athletes who are also on that start line. I’m sure they were equally jazzed to be at the Tour de France. But was it possible that they might not have grasped the entirety of that moment? So, I feel lucky that I got to see it from a variety of perspectives.

It was it was incredibly emotional all around, personally, professionally, as an athlete as an advocate. I’ll never forget any detail. Part of what I told myself was, “feel everything you can today, whether it’s tears of joy or exhaustion.”

But we have to be very careful that this doesn’t become tokenism. Like, “Oh, it worked. We’ve got women one day for women, that’s enough.” We’ve kept the pressure on saying it’s not enough. If your fans want more, your sponsors are reaping the benefits financially, and the athletes want more, if you have that trilogy in place, and it’s working, the fact that you’re not growing the race reeks of tokenism or apathy. The one-day race did finally change in 2022. We now have an eight-day race for women, which is great, but it’s still only one-third of what the men are doing.

What has been the impact of business and sponsors in growing women’s cycling? What are the next steps in terms of investing in women’s cycling?

The viewership has been phenomenal. One of the greatest parts is that cycling fans are tuning in because they love watching top level racing and they don’t care whether it’s male or female. They understand that sport is sport, and they want to tune in for the best of the best. What’s happening is that concept of a rising tide lifts all boats. Now, because we’re broadcasting the women, we are actually growing the spectatorship and the viewership of all of cycling.

So, the numbers are up, everything is huge, and where we need to keep the pressure on is that we don’t stay at eight days at the Tour de France for eight more years. And fans can play a huge role in this.

I love giving a few tips on how we, the general public, can actually use a term that I call benevolent shaming. That’s looking at the sponsors, the owners and the directors of the sport to say, “Amazing for the women to have eight days, however, shame on you for thinking the women aren’t capable of even completing 21 days. Shame on you for keeping the distance shorter, because you don’t think women can complete the distance. And shame on you for the fact that at the Women’s Tour de France, the women are earning 29% of what the men make.”

An important thing that I want to bring up about that point is yes, the women are racing eight days and the men are racing 21 days, but that 29% that I’m talking about, is specific eight days to eight days. I’m talking about what the men are earning for eight days to what the women are earning for eight days. And that’s not okay.

Where we can also direct a little bit of this benevolent shaming is to those sponsors who are onboard, they’re supporting a women’s race, but we’re not yet seeing equality in pay. We need to reach out to those sponsors and say, “I want to buy your product, I think what you’re doing for women’s cycling is great. But you’re in a position to make this prize purse bigger and better and stronger. And when you do, I will support your product.”

It’s what I like to call it the loophole of tradition. A lot of sponsors don’t think to ask where the women are because they either assume that it’s 2023 so of course, there’s a women’s equivalent. The race directors would naturally be bringing us that if it existed, wouldn’t they? It doesn’t cross their mind that perhaps whomever they’re talking to might be so old school or outdated that they’re not even bringing the pitch for the women’s inclusion to the table.

This happens a lot in sports, because when we look at something like cycling, which, over the decades has only really truly been televised on the men’s side, we begin to equate it as a male sport. When we bring in the marketing part and finally have the visibility and TV time for the women, it becomes a sport that both genders play. But until we have that leverage, there are things that remain men’s sports only in the public mind.

In 2017 you started the Homestretch Foundation to assist low-income female professional athletes and work for salary equity. What have you learned through this work?

We’re about to start our eighth season and to date we have helped 88 athletes from 18 different countries in women’s cycling as well as a few men who have come through our program. Primarily, what we’ve done is help these athletes who are already at the pro level or the very high elite level by providing them free housing, room and board for up to six months each year in Tucson, Arizona, which is kind of the mecca for road cycling training in North America. We’ve had six Olympians through our program, countless national champions, and it’s great to help another human being thrive and get to the next level. That feels great.

Then, behind the scenes, we fight to change that gender pay gap.

In cycling, our major league is the World Tour and our minor league is the Pro Continental level or Pro Conti. On the men’s side of the sport, there is a base salary for both the World Tour and the Pro Conti. And then of course, these athletes can make hundreds of millions on top of that base salary, but at least there’s a base salary in place.

For the women, there was no base salary at the World Tour or the Pro Conti level. What was happening was these athletes had to carry two, sometimes even three part time jobs, to be able to make it or they had to have financial support elsewhere, whether from spouses or family. And they were expected to do the same job as the guys, which is a very physical job when you talk about professional endurance sports.

Finally in 2020, and then moving up incrementally to 2023, the women at the World Tour now receive a base salary. Our impulse is to cheer, but the women on the World Tour are making the base salary of what the men at the Pro Conti level are making. And the Pro Conti women still have no base salary. That’s not okay. It almost falls back to that tokenism.

So back to what we do at Homestretch; we help the athletes who are here, but what we don’t want is a band aid situation of just helping these athletes and having this pro cycling gap wage gap go unnoticed. In fact, it’s our goal someday that we can close Homestretch down because women are being paid equally. We were created so that we could someday shut down.

What’s next for women’s sports? What’s flying under the radar that we should be paying attention to?

I think one of the most important things we can do is play the investigator role. Look at these amazing changes taking place in women’s sport, but let’s peel back the layers of this onion. What isn’t taking place? What can we shine a light? Where can we make change happen?

One of the things I think we should all pay attention to is the 2024 Summer Olympics, which will be in Paris. For many years, the International Olympic Committee has been touting this as the Equality Games – that women and men will be equal at this Olympics. I mean, that sounds like a great thing, because we all love equality and we want to see it happen, but is the IOC doing their due diligence? Is it really going to be equal?

I think it’s fun for fans of sport to put on their investigator cap and magnifying glass and take a look at what’s going on. Sometimes it’s surprising to people how far down the inequality can stem. In cycling, even our junior girls race shorter distances than our junior boys. Who put that rule into place? That is happening in other sports, too. Are girls and boys playing different times, or distances, because an old rule is still in place? I hope it can empower people to look at whatever sport they love most and see, is it as equal as we hope that it might be?

Then, if you do find inequity, know you also have the power to create that change. Take off the inspector hat and put on the advocacy hat – whether we’re talking about youth cycling at the 9- to 10-year-old level, or the World Tour and salary equity. Change must happen in all of these places.